Geologists have confirmed the discovery of rare humboldtine fragments at an excavation site in northern Chile, marking one of the few verified findings of the mineral in the modern scientific record. Humboldtine — an iron oxalate mineral formed under unique geochemical conditions — has long fascinated researchers because it can act as a historical fingerprint of ancient carbon cycles. The latest discovery could reshape our understanding of how carbon once moved through the landscape millions of years ago.

What Makes Humboldtine So Unusual

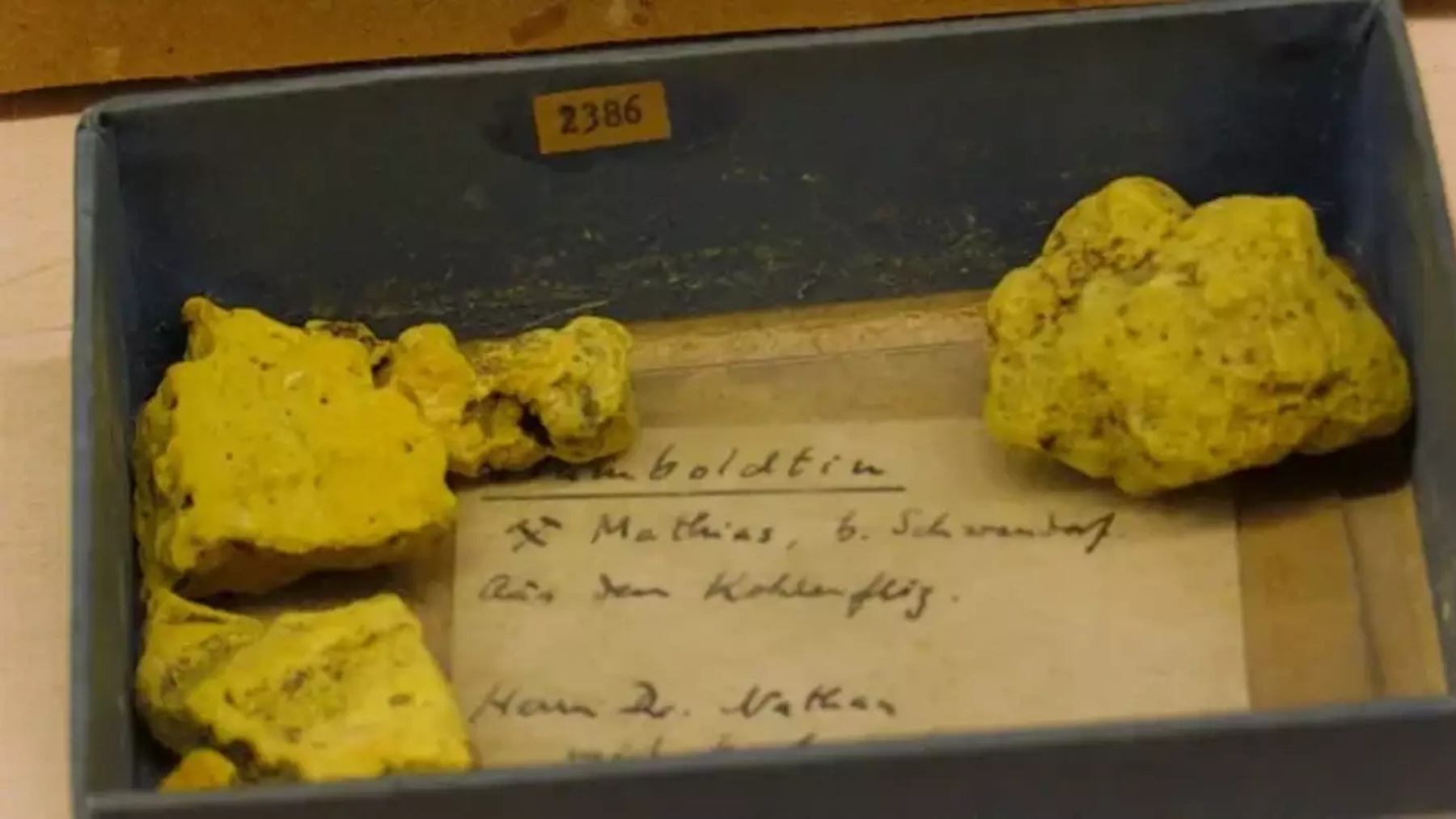

Humboldtine is incredibly rare in natural deposits. It is formed by the interaction of iron-rich sediments and decaying organic material, a combination that requires precise environmental chemistry to persist long enough to crystallize. Most of the time, humboldtine decomposes before it ever reaches detectable quantities, which explains why only a handful of documented samples exist worldwide.

The newly confirmed fragments were located during a routine mineral survey rather than a targeted search, echoing past accidental discoveries that have shaped mineralogy history. The find has already been compared to the surprise identification of organic-rich rock clusters described in EOSel’s recent coverage of Planet-Scale Ecosystem Twins and the evolution of geological digital modeling.

Where the Discovery Was Made

The fragments were identified in the Atacama highlands, a region known for its hyper-arid environment and high mineral diversity. The samples were found embedded in oxidized stratigraphic layers thought to date back 12 to 15 million years.

According to the Chilean Geological Survey’s preliminary field report, sensor-based spectral imaging initially labeled the fragments as a common iron compound. It was only after laboratory oxygen-isotope analysis that researchers confirmed the unique oxalate composition associated with humboldtine.

Why the Finding Matters for Climate Science

Humboldtine has a deeper scientific role than its rarity suggests. Because it forms only when iron minerals interact with organic matter under specific temperatures and acidity ranges, it can help reconstruct environmental conditions that no longer exist.

Geochemists say the fragments may contribute answers to several long-standing questions:

• How carbon once moved between soil, groundwater, and atmosphere

• Whether microbial ecosystems played a larger role in carbon sequestration than previously believed

• How ancient climatic shifts influenced mineral formation cycles

These insights connect directly to modern sustainability research. If humboldtine can be linked to historical forms of natural carbon capture, it may help refine models used to evaluate today’s carbon-sequestration strategies.

The Technology Used to Confirm the Mineral

To avoid misidentification, researchers ran three verification steps:

- Laser ablation spectroscopy to analyze trace elements

- Fourier-transform infrared scanning to identify organic functional groups

- Oxygen-isotope fractionation profiling to compare structural chemistry with confirmed humboldtine deposits

The testing process mirrors modern mineral-analysis workflows discussed in recent EOSel articles on AI-assisted ecosystem mapping and digital-twin environmental modeling. Several labs are now using machine-learning tools to analyze the digital spectra collected from the fragments.

Does This Discovery Change Geological Timelines?

Possibly. If additional humboldtine deposits are confirmed in the same stratigraphic region, researchers may need to revise existing models of carbon mobility during the Miocene epoch. That era saw major climate transitions affecting both vegetation and sedimentation — yet the geochemical signatures of those transitions remain poorly mapped.

A forthcoming peer-review paper is expected to propose that humboldtine findings may identify zones of high biological turnover, where climate conditions triggered rapid shifts in organic matter and mineral deposition.

What Comes Next for the Research Team

The fragments are now being digitized into an open spectral database so researchers worldwide can continue the study using high-resolution imaging. A small team from the University of Antofagasta is also returning to the site to extract additional core samples, with priority on deeper layers that may contain larger structures.

There is also discussion of integrating the discovery into global mineral-mapping networks and digital Earth platforms, allowing machine-learning models to search for similar signatures in other locations.

Conclusion

The confirmed discovery of humboldtine fragments is not just a mineralogical milestone — it is a window into Earth’s deep carbon story. Every rare occurrence of this mineral brings scientists closer to understanding how ancient life, geology, and atmosphere once interacted. Whether further sampling uncovers larger deposits or not, the finding reinforces how much of Earth’s climate history remains hidden in the layers beneath our feet.